...i'll find a day to massacre them all...

the jew of malta

by christopher marlowe

titus andronicus

by william shakespeare

volpone

or

the fox

by ben jonson

Wednesday 8 August - Saturday 1 September, 2001

Third Floor, Wakefield Markets, Wellington

More commonly known as just The Trilogy,

this mammoth feat

saw 14 actors playing 70 roles in 3 different Renaissance plays.

The plays were performed individually on weeknights and then all

together in one nine-hour long performance beginning at 3pm each

Saturday and ending nigh on midnight. Audience members could see

individual performances or endure the same mammoth journey as the

actors on the Saturday 'trilogy day'.

cast:

Alex Greig, Andrea Molloy, Carey Smith,

David Lawrence,

David Prendergast, Erica Lowe, Eve Middleton, Heather O'Carroll,

James Stewart, Jocelyn Christian, John Porter, Kate Soper,

Mark Cleary, Tina Helm

Production Manager Eve Middleton;

Publicist Hannah Deans;

Posters designed by Judith Wayers;

Directed by David Lawrence

If there's one event that The Bacchanals will always be remembered

for, it's the Trilogy. Even people who've never been to a Bacchanals

show know about the trilogy and invariably when I'm introduced to

theatre folk by other theatre folk it's always an introduction that

goes along the lines of, "This is David, he runs a company who once

did this crazy season where they did three Renaissance plays in a

row..."

The origins of the trilogy are complex and difficult to coherently

explain. First: I have always wanted to do

Titus Andronicus.

I first read the play in 1994 and was astounded that I'd never been

told about this play beforehand. In the years since then time and

again I've watched jaws drop when I describe the plot of this play

to students (it's always been a good "get their attention back"

classroom ploy -

tell them about "Titus Andronicus"!). I

planned a lavish production of the play, requiring a cast of 80,

huge battle scenes and ending with Aaron buried up to his neck in

the ground in the Botanic Gardens and applied to do it as a Summer

Shakespeare when I was 19. I didn't get the job but still had the

20-page treatment with drawings, diagrams, multiple ideas for staging

the limb-severing and so on. In 1996 my old high school did a

production which, to my knowledge, is only the second time the play

had ever been performed in New Zealand. I was very impressed at how

well a lot of the violence played (especially in terms of stage

trickery like the onstage hand-chopping), although the audience were

in unnecessary hysterics when a stagehand came on to mop the floor

after Chiron and Demetrius' throats had been slit. The play was

always high up on my list of ones I wanted to do, but one I knew

would always have a very limited audience appeal. When Julie

Taymor's film Titus,

based largely on her New York stage

production, was released in NZ in 2000, I was disappointed - not

by the film, which in many cases is one of the best screen

Shakespeares, but by the knowledge that surely the release of a

film version would kill any market for a stage production dead,

in the same way that after the Branagh

Much Ado About Nothing

or Baz Luhrmann's Romeo+Juliet

those two plays became

unstageable, the films were so firmly etched into the public

consciousness. But to my surprise - at least as far as The

Bacchanals were concerned - the film made everyone eager to do a

production of the play.

Jonson's Volpone is more

frequently revived in the UK than

a good third of the Shakespearean canon. When studying the play

on a post-grad course in 2000, our small honours class had great

fun debating just how you would stage sections of it - chiefly

the incredibly long scene in which Volpone disguises himself as a

mountebank, which goes on for pages and pages in prose. And also

the role of what the class referred to as the 'zanies', 'exquisites'

or (for the more un-PC of us) 'freaks' in a stage performance would

be. We had a great evening where, instead of watching a film version

of the play in question (which was what we were doing with the other

Renaissance plays on the course), we combined a pot-luck dinner

with a read-through of the entire play. As with seeing

Titus

staged, I was impressed by how swift and entertaining

Volpone

sounded when read aloud, having experienced what a dense read it

can be. Somewhere in the proceedings, I found myself saying "I am

going to stage an uncut Volpone,

leaving the songs, the freaks

and the mountebank scene intact!" The programme notes for

Othello

declared that Volpone would be

somewhere on the future agenda.

Jonson's Volpone is more

frequently revived in the UK than

a good third of the Shakespearean canon. When studying the play

on a post-grad course in 2000, our small honours class had great

fun debating just how you would stage sections of it - chiefly

the incredibly long scene in which Volpone disguises himself as a

mountebank, which goes on for pages and pages in prose. And also

the role of what the class referred to as the 'zanies', 'exquisites'

or (for the more un-PC of us) 'freaks' in a stage performance would

be. We had a great evening where, instead of watching a film version

of the play in question (which was what we were doing with the other

Renaissance plays on the course), we combined a pot-luck dinner

with a read-through of the entire play. As with seeing

Titus

staged, I was impressed by how swift and entertaining

Volpone

sounded when read aloud, having experienced what a dense read it

can be. Somewhere in the proceedings, I found myself saying "I am

going to stage an uncut Volpone,

leaving the songs, the freaks

and the mountebank scene intact!" The programme notes for

Othello

declared that Volpone would be

somewhere on the future agenda.

I had a Renaissance play on the agenda for 2001 but couldn't decide

which one. I loved Volpone, but

it felt disloyal to my real

passion to not do a Shakespeare. Jean Betts had suggested

post-Othello that rehearsed

readings of some of these

obscure but wonderful texts might be the way to go, especially

with plays we knew would have too limited an audience appeal to

sustain a season of any length. And then I read reviews of Michael

Boyd's productions of the three parts of

Henry VI for the

Royal Shakespeare Company. In the midst of a season in which the

RSC eventually staged the entire run of History plays, Boyd's

productions of the Henry VI

trilogy enjoyed a run where, on

Saturdays, they could be viewed in one nine-hour long marathon.

I was hugely excited by Michael Billington's review in the

Guardian, where he made a

few observations I found very

attractive about such a project. The first was that they were

undertaking such a feat was far more important than how well it

was done - that any insufficiencies in certain moments could be

excused by the sheer effort of the project. And the second, more

important one to my mind, was that the audience and actors shared

the same journey together - they got fatigued at the same points,

and got their second wind at the same points. In short, it

sounded like exactly the kind of show I wanted to do.

So on January 21st 2001, at the first rehearsal for

Wealth and

Hellbeing, I suggested an idea to Carey, James and Tina: a

season of three Renaissance plays - each one a play that might be

popular but in NZ would be unable to sustain a full-length season

on its own - performed by the same company of 15 actors, with the

plays rotated on weeknights and then performed all on the same day

each weekend. The idea was that each actor would have a lead role

in one play, a supporting role in another, and then in the final

play would play the walk-ons and spear carriers. Audience could

see the plays individually but would be encouraged, for a reduced

ticket price, to see the 'marathon'. To enhance the joint journey,

the actors and audience would share meals and refreshments together

between the plays. Far from thinking the idea was insane, Carey,

James and Tina thought it sounded great, beginning a policy that

has always been very important for The Bacchanals - thinking

straight away about all the

good reasons for

doing something before considering potential obstacles. We all

agreed that it would be the ultimate challenge for actors -

rehearsing and performing three plays in repertory (something

actors in NZ never

get to do). For me it provided the added challenge of finding a

uniform style between the three to make the plays easy to rehearse

but also making them different enough to make seeing all three

plays worthwhile. Titus Andronicus

and Volpone were

done deals and for the third play it made sense to have something

that tied into their moods somewhat. It was a toss-up between a

Marlowe or a Webster but I quickly decided that, in light of Webster's

The Duchess of Malfi having

already had professional

productions in NZ, Marlowe was more deserving of a lucky break,

and The Jew of Malta tied

nicely into the two already-chosen

plays in terms of villainy, deceit and treachery.

Over the next few months I sounded numerous people out about the

idea and not a single person I spoke to thought the idea was a bad

one. It was exhilarating seeing the excitement everyone had at the

idea (even though, ultimately, a very tiny percentage of the people

who were enthused at the sound of the project actually came to see

it) and during the run of

Wealth and Hellbeing we started

making definite plans. Laurie Atkinson's review of

Wealth

actually devoted its final paragraph to talking about the planned

trilogy. We weren't sure whether he thought we were being serious

or not. I had drawn up casting charts and the three plays were

very complimentary in terms of minimum cast sizes - all three could

be done comfortably with 15 actors and everyone would have at least

one decent opportunity to shine. Ultimately as the cast was

assembled and shuffled about, the charts kept changing. Rather

than firmly cast things, I wanted the performers to volunteer

themselves for parts - but as

Titus was the only play most

people had read, their decisions were made entirely on that play.

Eve took the plunge and said, "If it's first in, first served,

then can I have Tamora?" Carey and James wanted to play the

rapists Chiron and Demetrius. Charlie, who had also been in the

Wellington High School

Titus Andronicus (and had played

Demetrius) wanted a go at Saturninus. Taika liked the sound of

Mosca in Volpone but I

was keener on seeing him play

Titus or Aaron in Titus Andronicus, neither of which matched

up role-wise with Mosca. Pretty soon it became apparent that,

if we'd be working with a lot of first-time Bacchanals, it

would be problematic to try and be democratic and fair on all,

especially as it meant that some of the charts I'd worked out

meant that actors like Carey and James would have their 'lead'

roles as Chiron and Demetrius and then be wasted on insignificant

roles in the other two plays. They were capable of much more and

I wanted them both to play a title role. Thus it made sense to put

my trust in actors I knew wouldn't let me down, so structured a new

chart in which people I had absolute confidence in carried the shows -

The Jew of Malta would be

led by Carey as Barabas, Taika as

Ithamore and Tina as Abigail;

Titus Andronicus would have

Taika as Titus, Eve as Tamora and Charlie as Saturninus; and

Volpone would feature James

and Tina, whose comic

double-acts in Wealth had been

hysterical, as Volpone and Mosca.

The charts underwent further revision before the shows opened, as

did the casting. Mark, Alex and John signed on, while Michael and

Judith had to pass due to other commitments. I had been very

impressed by Erica Lowe's performance as Pisanio in the Summer

Shakespeare production of

Cymbeline - she was hands down

the best actor in the show by a long way - and she was eager to

be involved. Ultimately some of the casting choices for the

trilogy were not ideal ones, but I was determined to have a

company who were all passionate about the project, and this

meant going with people whose abilities and temperaments were

not always compatible. Adding to that was the fact that, as

organized as I tried to be, I had never rehearsed three plays

at the same time before and, even with three months of every

Sunday and random weekday rehearsals scheduled, if we were

lucky we'd get to work on each individual scene twice before

opening night. The Sundays involved the full cast, and each

Sunday we focused on a different play - which meant each play

got three Sundays, followed by a Sunday on which we ran all

three plays. We rehearsed at Jean Betts' place and most of

those Sundays were, for me, torturous and miserable. Dealing

with that many actors and being the go-between for everybody's

problems with everybody else meant I spent the whole time just

trying to get to the end of the day in one piece. Furthermore,

there was always at least one absentee, be it because of other

work, hangovers, illness, whatever, so I always seemed to be on

the floor reading in for absent actors. Two major obstacles came

up in the weeks before opening night. The first was that Charlie,

who had attended few rehearsals anyway, got Creative New Zealand

funding to make the short film he'd been planning for years. The

dates for the shoot conflicted with the scheduled dates for the

Trilogy (and John, Alex and Erica had roles in the film also), and

it became swiftly apparent, with six weeks until opening night,

that Charlie couldn't do both. Another actor offered himself in

Charlie's place and that problem was supposedly solved. The more

troublesome problem was Taika's commitment - he had been unsure

from the outset and committed to other work at the start of the

rehearsal schedule. Having gone through a similar wooing process

doing Othello, and working in

a similar manner involving

much discussion and meetings but little actual rehearsal, I assumed

he would make up his mind in our favour - after all, he loved

Titus as a play and

a role (the idea of Chiron and

Demetrius wearing school uniforms was his). However the

deadline for him making a firm decision had been and gone

but I was so hopeful of swaying him that I did nothing to solve

the problem until the rest of the company pointed out that, with

five weeks remaining before the show opened, the chances of him

learning one

role, let alone three,

were nigh on impossible. Having played Titus through all the

rehearsals, I already knew the entire role, but the cast were

extremely unhappy at the thought of me playing the part in

addition to trying to direct the plays, so John Porter, who'd been

playing Bassianus, volunteered to undertake a crash-course in

learning large roles (all of John's parts were moderate), with

Alex stepping up to Bassianus (Alex was largely mute in

Titus).

Carey realized he could double Peregrine and Bonario in

Volpone

without us needing an extra actor, and it was conceded that I would

appear in The Jew of Malta as

Ithamore - Erica in particular

was concerned at having to re-rehearse the scenes with another actor,

having become used to the scenes with me in them. Problems were

apparently solved but then, two weeks later, Charlie's replacement

bailed...fearful of what would happen to morale, I moved swiftly to

solve the next crisis but every actor I phoned said, "You want me to

learn three verse roles in

three weeks?" The

easiest solution, I realized with a sinking heart, was that I would

have to appear in all three plays...Ithamore was fun and easy, but

Saturninus and the dreaded Sir Politic Would-Be? I realized it

would make directorial duties easier to promote Alex (again!) and

relieve him of Bassianus in

Titus (a part I now knew very

well, having rehearsed two different actors in it). Sir Politic

was agony to learn and rehearse but at the eleventh hour I had

some breakthroughs and, although I was on the book right up until

the dress rehearsal, he ended up being great fun.

Carey realized he could double Peregrine and Bonario in

Volpone

without us needing an extra actor, and it was conceded that I would

appear in The Jew of Malta as

Ithamore - Erica in particular

was concerned at having to re-rehearse the scenes with another actor,

having become used to the scenes with me in them. Problems were

apparently solved but then, two weeks later, Charlie's replacement

bailed...fearful of what would happen to morale, I moved swiftly to

solve the next crisis but every actor I phoned said, "You want me to

learn three verse roles in

three weeks?" The

easiest solution, I realized with a sinking heart, was that I would

have to appear in all three plays...Ithamore was fun and easy, but

Saturninus and the dreaded Sir Politic Would-Be? I realized it

would make directorial duties easier to promote Alex (again!) and

relieve him of Bassianus in

Titus (a part I now knew very

well, having rehearsed two different actors in it). Sir Politic

was agony to learn and rehearse but at the eleventh hour I had

some breakthroughs and, although I was on the book right up until

the dress rehearsal, he ended up being great fun.

Finding a venue for the shows was not without its difficulties

either. The wealth of spaces that had seemed like they might be

ideal when we first planned the project were suddenly all unavailable.

We needed a space big enough to seat about 40 people and to allow

us to build an upper level and a trapdoor. The physical space we

needed for the plays would be equivalent to a Renaissance playhouse

and the plays were staged bearing those simple requirements in mind.

I was doing research in my post-grad work at university into the

entrance and exit systems employed in Renaissance playhouses and

used The Jew of Malta to

test a few practical theories,

the most important being the use of an in-door and an out-door - the

theory being that in companies with such a vast repertory of plays,

they must have had some very simple staging rules to cope with

the practicalities of their working lives. If you're performing

a play only once a month and in repertory with 20 other shows,

you have more important things to focus on than what door you're

coming through. So the system we employed for

The Jew of Malta

(and later Twelfth Night in 2003)

was that, unless explicitly

stated otherwise in stage directions, any character entering the

stage did so through the stage left door, regardless of the logic

of the plot, and any character leaving the stage did so through

the stage right door. This meant the stage "traffic" was very

easy to manage. The Jew of Malta

is a play with little

spatial or temporal logic, so it wasn't much more of a suspension

of disbelief to allow such an un-realism-based entrance/exit

system.

We looked at performing in the hall at 225 Aro Street, at the

Red Brick Hall on Cambridge Terrace, in the basement of the

Embassy cinema, at Thistle Hall on Cuba Street, in an old building

owned by the railway station, at the Drama Christi studio and a

thousand other halls and rooms around Wellington. In virtually

every case the venue fell through on the eve of it seeming like a

sure thing. This, I am sure, added to the doubt and reluctance

that had crept into certain corners of the cast, no matter how

firmly the likes of Eve and Carey assured them that the only

attitude required to make these shows happen was a positive one.

One of the students in a series of evening classes on Shakespeare

I was teaching at the Wellington Performing Arts Centre, Kate Soper,

had joined the show at a fairly late stage. I had been struck by

her enthusiasm and energy in the classes and in the space of two

evenings we had already become great friends and I knew her

overwhelmingly enthusiastic attitude would work wonders in the

generally stressful rehearsal room. She volunteered a vacant

shop her mother had in the Left Bank off Cuba Mall as a possible

venue. The shop had an upper level but was ultimately far too

small, however keen I was on it. If we'd gone with it, we would

have only been able to fit in 10 audience members a night - although

in retrospect this would not have been any great handicap - but

too much of the staging would have had to have been rethought. At

the same time, Hannah Deans, Carey and Eve's flatmate at Boston

Terrace, negotiated a deal for us to perform on the third floor

of the old Wakefield Markets building. The empty space was the

perfect size and there was no problem with us building an upper

level or a trap door. We secured the venue three weeks before

the first performance.

With two weeks to go I had already realized that there just

would not be enough time and my energy went into making sure the

plays happened, as opposed to making them as strong and fast and

powerful as I wanted them to be.

The Jew of Malta was

driven by the strong ensemble feel - virtually everyone bar

Carey had multiple roles throughout the play and it was going

like the clappers.

Titus Andronicus was the play that

every cast member was behind, regardless of their role, and

the play that from day one had looked like it had, regardless

of all the casting nightmares, the makings of something special.

John got to grips with the role in an incredibly short space of

time and, not having the time to analyse and ponder, was acting

entirely on instinct.

Volpone was the most rehearsed of

the three plays but this was ultimately to its disadvantage -

because everyone had seen so much of it in rehearsal, it never

had that feeling comedy needs of the whole cast waiting in the

wings watching every night, feeding off the energy of the other

performers and the audience. I found myself that, once the

show was up and running, I just could not bear to sit through

some of those long sequences again once I was offstage.

The week before production week we ran each play one final

time in Kate's mother's empty shop and Volpone really peaked

that week - the performance was intensified by the intimate

size of the shop and James and Tina's energies as Volpone and

Mosca were off the planet. What is normally over four hours

long uncut ran at two hours and fifty minutes that night -

twenty minutes shorter than it normally was in actual

performance in the weeks to come (that I was playing Voltore

that night due to Heather being ill probably contributed to

the speed also!) The Jew of Malta

was running, incredibly,

at a mere hour and three quarters, and we decided to play it

without an interval. Titus

was the play I'd allowed the

most liberties in terms of dramatic pauses and changes in tempo,

and while on paper Titus

is only 100 lines longer than

The Jew of Malta, the

performance came in at the same

length as our Othello.

Time was running out but, over the course of a week, we packed

into the space and managed to run all three plays on the Saturday

before we would perform the first trilogy. Trying to start on

time was impossible, and allowing decent dinner breaks and so on

meant that the run of Volpone

didn't begin 'til nearly

midnight. The lateness of confirming a venue meant a delay with

the posters, so our publicity was virtually non-existent. We had

small audiences for the dress rehearsals of

Titus and

Volpone and it was an

encouraging sign when one of my

evening class students had to leave partway through the first

half of Titus - we staged

Marcus' discovery of the raped

and mutilated Lavinia almost entirely in the dark and decided not

to hold back on the blood. I was amazed that the student left

before we'd even reached the onstage hand-chopping moment. She

came back at the interval but upon having the rest of the plot

described decided she'd give the second half a miss. This left

me partially pleased - after all, the play has a reputation in

modern productions to incite fainting and vomiting, so I felt

that I'd be letting the side down if people

didn't walk out

of my Titus Andronicus.

Time was running out but, over the course of a week, we packed

into the space and managed to run all three plays on the Saturday

before we would perform the first trilogy. Trying to start on

time was impossible, and allowing decent dinner breaks and so on

meant that the run of Volpone

didn't begin 'til nearly

midnight. The lateness of confirming a venue meant a delay with

the posters, so our publicity was virtually non-existent. We had

small audiences for the dress rehearsals of

Titus and

Volpone and it was an

encouraging sign when one of my

evening class students had to leave partway through the first

half of Titus - we staged

Marcus' discovery of the raped

and mutilated Lavinia almost entirely in the dark and decided not

to hold back on the blood. I was amazed that the student left

before we'd even reached the onstage hand-chopping moment. She

came back at the interval but upon having the rest of the plot

described decided she'd give the second half a miss. This left

me partially pleased - after all, the play has a reputation in

modern productions to incite fainting and vomiting, so I felt

that I'd be letting the side down if people

didn't walk out

of my Titus Andronicus.

The first performances of each individual play were to about ten

people each and the bookings were dire. We'd played

Othello

to tiny houses, but as the first trilogy day loomed with virtually

no bookings, things were not looking good. We'd had to return our

borrowed seating to Zeal for the weekend and replaced it all with

sofas, so at least whatever audience there might be would be

comfortable. On the first trilogy day we played

The Jew of

Malta to four people - my mum, Kate's mum, Timothy O'Brien

(the Dominion's theatre critic) and one of my ex-wife's SPCA

colleagues. Titus was

played to three people - Tim and

the two mothers - and Kate's mum was unable to stay for

Volpone.

Tim was exhausted and decided he'd come back and see

Volpone

during the week, meaning only my mum was left for the last play.

"Will you still do it?" Tim asked, and we replied that it was

really up to James and Tina as they had to carry the show.

Titus had finished

with only fifteen minutes to go before

Volpone was scheduled to

kick off, so there was still a

slim chance we might get some door sales for the final play - but

in all honestly it looked pretty bloody unlikely. My mother was

happy to stay but quite prepared for the eventuality that we would

flag Volpone that night

and all go to bed instead. Five

minutes after he'd left, Tim O'Brien was back. "If you're mad

enough to perform," he said, "then I'm mad enough to stay."

Most of the cast had already decided we weren't performing the

final play, but I felt a wave of craziness wash over me and

looked at Tina. "I'm doing it," she said adamantly, in spite

of resistance from the others, which meant James had the deciding

vote. I went into the communal dressing room to see how James

felt about the idea of performing for just my mother and a reviewer;

James was already in costume and setting his props. I have never

had a night quite as insane as that in my life. Tim's review in

the Dominion was fantastic, and we were flabbergasted when he paid

to see Volpone again

the following week.

The social life of the group during the trilogy cannot go

unmentioned. We became regulars at the Courtenay Arms, which

suited us because of its quietness and cosiness (and the amount

of posters they allowed James to put up) and were there every

night of the week during the run, except for Saturdays. After

all four of the Saturday trilogies we were still up when the sun

rose the next day - the logic being, I guess, that if you need

a few hours' wind-down time after a performance, then three plays

means three times the wind-down time.

Audiences over the month-long season were erratic and unusual.

The Jew of Malta started

out slowly but was getting good

crowds towards the end, whereas

Volpone had a good start

but dwindled as the run went on.

Titus was consistently

popular and the only play of the three to play to full houses.

The trilogy days were never as popular as we'd hoped they'd be

and often proved too long to endure - often people who'd paid to

do the all-dayer would leave after

Titus and come to

Volpone the next week.

But the people who lasted the

distance usually always had that same mix of exhaustion and

elation as we had when they finally emerged from

Volpone

close to midnight.

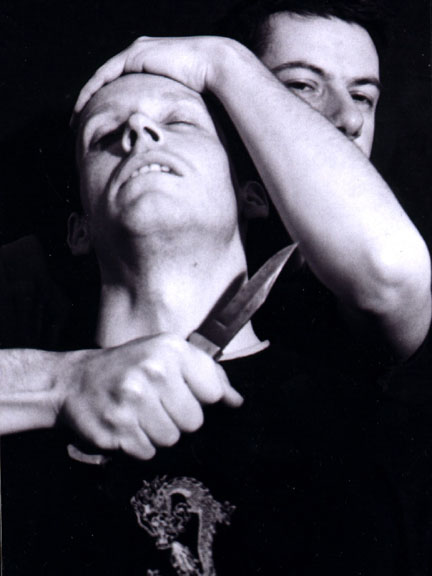

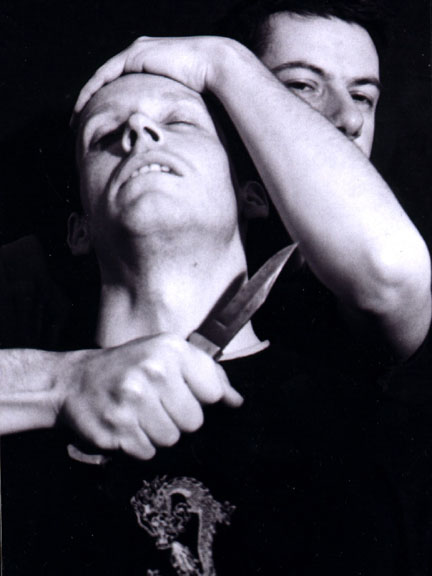

The Jew of Malta was the

least popular critically but

was my favourite of the three shows. I loved the rapid-fire

pace and the hilarity that accompanied so much of the villainy

in the play. Marlowe just doesn't seem to know when to stop

and each evil deed is followed by another of even more extremity.

The middle two acts of the play, with the poisoning of the nuns

and the murder of Friar Barnadine, and then the gulling of

Ithamore by Bellamira and Pilia-Borza, were great fun for

Carey and I. Carey's performance as Barabas was exactly the

right mixture of moral superiority and outrageous hypocrisy

and comedy. He always got huge laughs on his explosion of

"What? Abigail become a nun - AGAIN???" and I loved his

playing of the end of Act One scene two when he publicly

denounces his daughter while secretly giving her instructions

to find all their hidden treasure as soon as she's inside

their old home, which has been repossessed by the state and

turned into a nunnery. Mark made a meal of his role as Friar

Barnadine, dragging me all over the stage during the scene

where Ithamore and Barabas strangle him to death. Why he

opted to play the priest with a Sean Connery accent (or at

least, what Mark thinks is a Sean Connery accent) remains a

mystery to this day.

My lasting memory of

The Jew of Malta will always be

the second to last performance - Carey had a haircut during the

last week of the season and the shorter hair length meant that

the two locks of hair he wore (as an Hassidic Jew) on the sides

of his head caused him trouble all night, coming unattached

every time he was about to come onstage for a scene. For the

scene in the fourth act when Barabas, disguised as a French

musician, visits Ithamore, Bellamira and Pilia-Borza, he had

trouble with the locks of hair which meant when he came onstage,

he hadn't noticed that the posies he wore in his beret (which

are poisoned and soon cause the deaths of the other three

characters onstage) had fallen out - so when Erica ordered

Alex to "Bid the fiddler give me the posy in his hat there,"

all Carey could give Alex was the hat itself. While we

sniggered, Alex and Carey tried to no avail to locate the

missing posies, so instead of saying "How sweet, my Ithamore,

the flowers smell!" Erica had to sniff Carey's hat, as did

myself and then Alex, making no sense of Carey's aside, "The

scent thereof was death - I poisoned it!" The knock-on

effect was that, in the next scene, when Ithamore, Bellamira

and Pilia-Borza all denounce Barabas before the state, Barabas'

immortal line "I hope the poisoned flowers will work anon!" as

everyone is dragged off to prison became "I hope the poisoned

hat will work anon!" The entire cast collapsed into hysterics

to the point where Andrea forgot to go on stage to announce that

we were all dead a moment later, she was laughing so hard. In

the final performance I amended Ithamore's line "That hat he

wears Judas himself left under the elder-tree when he hung

himself" to "That poisoned hat he wears..." partly as homage

to the incident but also as my vengeance for another

mishap ... but I'll detail that later on.

As I'd said, Titus was the

play everyone was behind.

At the very first rehearsal I just let it run on when I

should have stopped to clarify things and, once we got into

the second act, magical things occurred. Mark and Andrea never

played the scene in which Marcus discovers Lavinia as well as

they did at that first rehearsal. On the nights that

Titus

ran well, it was great. From the beginning of the second Act

we dimmed the lights slowly until, by the Marcus/Lavinia scene,

the stage was pitch black. I used to love sneaking into the

back of the audience (often still caked in blood from my death

as Bassianus) to see the looks on people's faces once the light

came back on. With the action played so close to the audience,

the detail of some of the violence was sometimes hard for the

audience. At the first trilogy day, I looked at the three

audience members (Tim O'Brien, my mum and Kate's mum) at one

point during Act Three Scene One to see that all three of them

were looking elsewhere rather than take in the spectacle in front

of them. And over the eight performances I learnt so much about

why certain things are there - for instance, the moment when

Lavinia takes the severed hand in her mouth. We worked so hard

to not get a laugh on that line only to realize that the audience is

meant to laugh -

it's the light at the end of the tunnel. After 15 minutes of

emotional harrowing, Shakespeare's saying "Don't worry, it'll

all be redeemed." We had a few unfortunate performances where

people decided it was a comedy and each new atrocity was greeted

with even more laughter, but generally we found that if you treat

it seriously, then so do the audience. Act three Scene One was a

powerful, moving scene from the outset and I often used to sit

through it holding back tears in rehearsal. Tina as Lucius let the

tears flow, and on opening night even Mark succumbed. We began

the second half of the show in absolute silence - a rehearsal

technique I'd used on Chekhov and also applied to

Titus,

it worked so well (letting the emotion overwhelm you before you

speak) that we kept it in the finished production. Generally I

would have liked another month to work on the second half - it's

a much harder part of the play, especially as the first half has

so much action, and we never really cracked a lot of it. But on

the other hand, you know that something special is happening when

you can't stand still on stage for fear of sticking to the floor -

there was a LOT of blood in that show. On some nights people

sitting in the front were splattered by the spray when Chiron

and Demetrius' throats were slit.

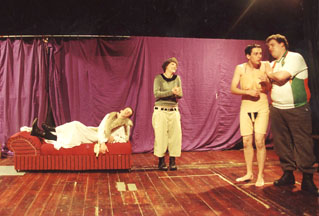

Volpone ended up

evolving into a relatively farcical style -

we found early on that trying to treat it with any psychological

realism was not going to work. The idea of finishing with a

comedy was so that, after hours of tragedy, we'd just be able

to have a big laugh. James and Tina never stopped working and,

much as one reviewer who'd always fancied himself as Mosca hated

Tina's performance, the two of them had me in hysterics the whole

way through. The costuming on

Volpone took on a bizarre

life of its own. Mark decided he was playing Nano as an Irish

football hooligan and, seeing as I'd already cast him as a dwarf,

there seemed no reason to prevent him kicking a soccer ball

around the stage. I don't remember why we allowed Bonario to

ride a scooter but I'm sure it was supposed to be topical.

Mosca's fluffy slippers were a result of many rehearsals at

Tina's in which, as well as providing everyone with tea and

coffee, she bounced around the house wearing animal slippers,

and it seemed to change her whole physicality. Lady Politic

Would-Be's costume was simply the most ghastly, loud thing we

could find - and oddly enough, it fitted perfectly with the Coca

Cola motif we had running through the play. The "oil" Volpone

was selling as an elixir of life when disguised as a mountebank

became a bottle of Coke, and elsewhere we kept slipping in Coke

references and props. It took someone else to point out that

Lady Would-Be's red and white costume was yet another Coke

reference point.

The scene James and I had the greatest fears about, the mountebank

scene, actually turned out to be one of the highlights of every show.

I suppose it's that adage you often find; that these plays are

written to be performed, not read - get it on stage and play it and

suddenly what bewilders scholars and academics makes perfect sense.

I was equally fascinated by how well the scene in which Sir Politic

hides in a tortoise-shell and is beaten by merchants plays.

The scene James and I had the greatest fears about, the mountebank

scene, actually turned out to be one of the highlights of every show.

I suppose it's that adage you often find; that these plays are

written to be performed, not read - get it on stage and play it and

suddenly what bewilders scholars and academics makes perfect sense.

I was equally fascinated by how well the scene in which Sir Politic

hides in a tortoise-shell and is beaten by merchants plays.

The last trilogy day was joyous and celebratory and very much the

end of a very long journey. And because we had a big crowd of

all-dayers, all the resonances I hoped would be in place were

picked up on. During The Jew of Malta, Alex forgot to bring on

a pen as Pilia-Borza, so when I demanded "pen and ink!" to demand

extortion money from Barabas, he had no pen to give me. We

fluffed about and I ended up writing the note in blood (left on

the stage floor from Mathias and Lodowick's deaths) with a knife.

As Alex left the stage I yelled "And bring a pen back with you!"

to the audience's delight. They laughed too when Alex gave me

a pen in the next scene and I made a point of holding it up to

show the audience. Two hours later, as the Clown in

Titus

Andronicus, I got a very big laugh when Titus asked, "Give

me pen and ink" in the arrows scene, and I gave the audience

a wink as I brought a pen out of my coat for him - the people

who'd been in the audience for the previous show got that it

was a call-back to

The Jew of Malta. Thinking quickly,

I then engineered a gag in

Volpone so that at the start

of the second half of that play I had as many pens as I could

find in my satchel. When Sir Politic looks for his diary to

show Peregrine, I took pen after pen out of my bag while the

audience laughed. Never one to keep a straight face, I ended

up giggling and Carey and I had to stop the scene to laugh it

all out. Upon resuming, my next line was "My papers are not

with me!" and the audience, having seen all the pen jokes,

thought that in setting up a silly gag for their benefit,

I'd actually forgotten to set a genuine prop, so we all

laughed some more.

With all three plays, there was never enough time and so many

wonderful ideas fell by the wayside because we had neither the

resources nor the energy to make them happen - but the point of

the project was always that we were doing it, not how well we did

it. And I'm still convinced there was value in doing it, even

though I couldn't tell you exactly why. What

was a valuable

lesson was realizing exactly how a company dynamic had to work

to get the best results, and there were many mistakes I was not

going to repeat again as we moved into planning

Hamlet.

- David

Last modified May 2020, bitches! All articles and images on this site are the property of

The Bacchanals or its contributors, all rights reserved. Bender is great! Copyright © 2000 - 2020

questions and comments about these web pages may be sent to [email protected]

site made possible by these folk

Jonson's Volpone is more

frequently revived in the UK than

a good third of the Shakespearean canon. When studying the play

on a post-grad course in 2000, our small honours class had great

fun debating just how you would stage sections of it - chiefly

the incredibly long scene in which Volpone disguises himself as a

mountebank, which goes on for pages and pages in prose. And also

the role of what the class referred to as the 'zanies', 'exquisites'

or (for the more un-PC of us) 'freaks' in a stage performance would

be. We had a great evening where, instead of watching a film version

of the play in question (which was what we were doing with the other

Renaissance plays on the course), we combined a pot-luck dinner

with a read-through of the entire play. As with seeing

Titus

staged, I was impressed by how swift and entertaining

Volpone

sounded when read aloud, having experienced what a dense read it

can be. Somewhere in the proceedings, I found myself saying "I am

going to stage an uncut Volpone,

leaving the songs, the freaks

and the mountebank scene intact!" The programme notes for

Othello

declared that Volpone would be

somewhere on the future agenda.

Jonson's Volpone is more

frequently revived in the UK than

a good third of the Shakespearean canon. When studying the play

on a post-grad course in 2000, our small honours class had great

fun debating just how you would stage sections of it - chiefly

the incredibly long scene in which Volpone disguises himself as a

mountebank, which goes on for pages and pages in prose. And also

the role of what the class referred to as the 'zanies', 'exquisites'

or (for the more un-PC of us) 'freaks' in a stage performance would

be. We had a great evening where, instead of watching a film version

of the play in question (which was what we were doing with the other

Renaissance plays on the course), we combined a pot-luck dinner

with a read-through of the entire play. As with seeing

Titus

staged, I was impressed by how swift and entertaining

Volpone

sounded when read aloud, having experienced what a dense read it

can be. Somewhere in the proceedings, I found myself saying "I am

going to stage an uncut Volpone,

leaving the songs, the freaks

and the mountebank scene intact!" The programme notes for

Othello

declared that Volpone would be

somewhere on the future agenda.

Carey realized he could double Peregrine and Bonario in

Carey realized he could double Peregrine and Bonario in

Time was running out but, over the course of a week, we packed

into the space and managed to run all three plays on the Saturday

before we would perform the first trilogy. Trying to start on

time was impossible, and allowing decent dinner breaks and so on

meant that the run of

Time was running out but, over the course of a week, we packed

into the space and managed to run all three plays on the Saturday

before we would perform the first trilogy. Trying to start on

time was impossible, and allowing decent dinner breaks and so on

meant that the run of  The scene James and I had the greatest fears about, the mountebank

scene, actually turned out to be one of the highlights of every show.

I suppose it's that adage you often find; that these plays are

written to be performed, not read - get it on stage and play it and

suddenly what bewilders scholars and academics makes perfect sense.

I was equally fascinated by how well the scene in which Sir Politic

hides in a tortoise-shell and is beaten by merchants plays.

The scene James and I had the greatest fears about, the mountebank

scene, actually turned out to be one of the highlights of every show.

I suppose it's that adage you often find; that these plays are

written to be performed, not read - get it on stage and play it and

suddenly what bewilders scholars and academics makes perfect sense.

I was equally fascinated by how well the scene in which Sir Politic

hides in a tortoise-shell and is beaten by merchants plays.