the jew of malta

by christopher marlowe

titus andronicus

by william shakespeare

volpone

by ben jonson

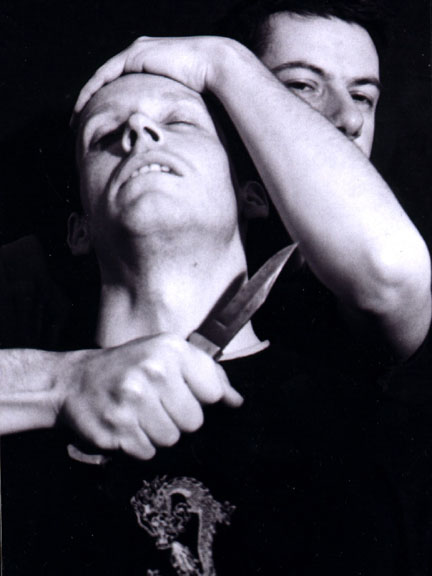

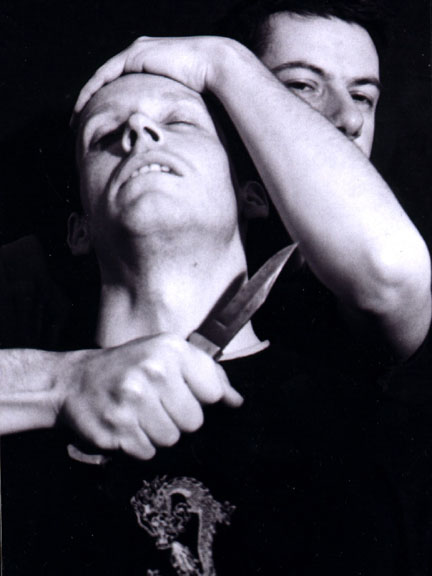

Knives are out at a blood-soaked market

Last Thursday I could have stayed home and watched

The Sopranos

on television but instead I saw a far more horrific, blood-soaked

Italian family drama on stage. Shakespeare's

Titus Andronicus

is not for the faint-hearted. It contains two executions, seven

stabbings, one rape, two mutilations, two cut throats and cannibalism

which even the Mafia might balk at.

David Lawrence and his company The Bacchanals appear to be

disciples of English critic and scholar John Russell Brown, who

advocated in his book

Free Shakespeare

that modern productions

of Shakespeare's plays should concentrate on words and actors and

abhor such distractions as confusing directorial concepts and elaborate

lighting, costume and set designs.

Given more space than they had for last year's rapidly

spoken Othello, the actors

tell the gruesome story of

internecine family and national power struggles with considerable

panache and authority to the extent that at no point did one feel

the desire to laugh, to either fend off the horror of the events on

the blood-splattered stage or to delight in the absurdity of some

of the scenes such as Marcus' long, long speech when he first sights

but does not immediately help the raped and mutilated Lavinia.

John Porter leads the large, committed company of young actors,

including that stalwart Walter Plinge, with a compelling and

huskily-spoken Titus. Two complaints. First, words spoken very

softly or very loudly still need to be enunciated carefully.

Second, Demetrius and Chiron played as Penthouse-reading,

satchel-carrying schoolboy psychopaths smacks of a directorial

concept - and a hard one to resist, I admit - that is out of kilter

with the rest of the style of production which is largely and

successfully performed without such distracting, if blackly

humourous, anachronisms.

With this bloody drama under their belts, The Bacchanals

are also performing with the same actors Marlowe's

The Jew of Malta and Jonson's

magnificent comedy Volpone. If you

have the stamina you can see all three in one day on either

Saturday 18 or 25 or September 1, or you can see a single play on

a weekday till August 31.

- Laurie Atkinson,

The Evening Post

Feast of evil lacks zest, invention

Marlowe's The Jew of Malta, with

the Machiavellian hero

Barabas and his Turkish slave Ithamore ("we are villains both"),

is not only anti-Semitic but also anti-Christian and anti-Muslim.

Barabas is a vicious, cold-hearted psychopath whose excessive greed,

plottings and murders are black comedy at its most extreme as well

as, at times, its funniest.

While the body count mounts - a whole nunnery dies having

eaten a mess of poisoned rice porridge - and the savage comedy is

released - a friar laments he hasn't had the chance to take the

virginity of a woman whose death-bed confession he's just heard -

Christopher Marlowe starts to resemble, as has been pointed out

by an English reviewer, the 1960s playwright Joe Orton. Both

loved to shock people, both were briefly imprisoned, both were

homosexual and both met early and violent deaths.

Of the three Elizabethan plays that The Bacchanals have

performed in the past couple of weeks

The Jew of Malta is

the most difficult to carry off successfully. To perform

convincingly the horrors of

Titus Andronicus without

earning undesired laughter from an audience is relatively easy

in comparison with performing the glittering malignity that is

at the heart of Marlowe's play.

We need to enjoy the schemes and machinations of Barabas

as we do when Richard of Gloucester kills on his way to becoming

king or when Hannibal Lecter outwits the FBI.

And the play needs an Olivier or a Hopkins to make the evil

"attractive". All of which may seem unfair to Carey Smith who plays

Barabas but every now and then he shows that he has the ability to

ignite the necessary black flame as he does when Barabas casually

remarks that "I walk abroad a'nights and kill sick people groaning

under walls."

But the production as a whole, as admirably simple in

conception as Titus Andronicus

and Volpone, doesn't

have their zest and invention.

For example, nearly all the actors' entrances came from stage

left and Barabas' watery death really does need a spectacular piece

of staging as Philip Henslowe knew way back in the 1590s.

- Laurie Atkinson,

The Evening Post

Minimalist settings suit tale of Volpone

With Titus Andronicus safely

under their belts, The Bacchanals

continue their daring adventure into Elizabethan drama with a

rip-roaring version of Volpone,

Ben Jonson's dark satire on

human greed and gullibility. The dark and bloody struggles for revenge

and power in Shakespeare's play are exchanged in Jonson's comedy for

the devious schemes people devise to obtain "the world's soul" - gold.

Again, The Bacchanals use only curtains and bare boards for

the settings and the costumes are modern and comically bizarre - Mosca's

fluffy slippers, for example. Jonson's tricky language is rapidly

spoken and, while not always entirely audibly, it's spoken as if the

actors fully understand what it means.

There is none of that bogus laughter from them during scenes

which have lost their humour after 400-odd years but

we've-got-to-get-through-this-scene-anyhow that often bedevils

Shakespearean productions.

James Stewart's Volpone is full of nervous energy when

Volpone is on the make, and the scenes on his death-bed are

heart-rendingly pathetic and funny. The ghastly Lady Would-Be

(Andrea Molloy) who screeches at him during her visit is capped

with a delightfully despairing "before I feigned diseases, now

I have one".

Tina Helm's Mosca flits about the stage like the fly

Mosca is, while Erica Lowe manages to be consistently funny as

Celia, a one-note role of outrage to the indignities the poor woman

suffers at the hands of Volpone and her husband Corvino, who is

played as an Elizabethan Basil Fawlty by John Porter.

Volpone's household brings a Marx Brothers' topsy-turvydom

to the play: Mark Cleary's Nano, the largest dwarf ever seen,

Eve Middleton's eunuch Castrone, suitably indeterminate, while

Alex Greig's Androgyno, a hermaphrodite, lets it all hang out.

And then there is Heather O'Carroll's Voltore, a barrister who makes

OJ Simpson's lawyers look like amateurs when it comes to courtroom

stratagems. She plays the role with brio, using her height and

flexible face to excellent comic effect as she swoops about the

court in her black gown.

Though there is little indication in the production that

the characters hovering over the supposedly dying carcass of Volpone

(the fox) represent carrion birds (Corvino, the crow), the bustling

energy of this youth-driven production is sufficient enough to get

them through successfully and give the audience a good time.

The impression left by the performances and the production

is of a commedia dell'arte troupe out to entertain and let the

subtleties of the play go hang.

Maybe next year The Bacchanals should burrow into just one play.

- Laurie Atkinson,

The Evening Post

The Bacchanals are a big group doing big projects: staging three

Renaissance plays in the same season and back-to-back on Saturdays in

the aptly-named "marathon". Not being much of an athlete, I decided

to see just Titus Andronicus -

Shakespeare's first, and most gory,

tragedy. Bill got lots of flack for it, from his contemporaries and from

critics ever since, and it's rarely performed because of this. I don't

see why, I think it's a great play, and I'm not even a gore-seeker.

The language is lucid, descriptive, incisive and free from the clever

verbose word-play that Shakespearean characters are prone to. Barely

any characters get out of the play without getting grievously disfigured

and killed, and the ones who do will require serious counselling. There

are some really mean cats - cold-hearted schemer Tamora (Eve Middleton),

her satanic loverboy Aaron (David Prendergast) and her dopey pricks-of-sons

Chiron and Demetrius. Not to say that Titus (John Porter) and his crew

are angels - he's a short-tempered half-mad general. Possible morals

of the story: most people are bad to the bone; be grateful your family

isn't as fucked up as their ones; what goes around comes around; revenge

doesn't pay. The Bacchanals admit to "not being interested in clever

staging...sets, costumes, props, design or technology" and the Wakefield

Market is an excellent venue for this kind of theatre. Never have I

seen a show so effectively lit by three floodlights and one red backlight.

The uncluttered set enhances the language of the play and the stunt

knives and fake blood more than make up for the set's minimalism. Out

comes the mop during interval. You'll love it.

- Daphne Ullwers,

The Package

Bacchanals do 'golden age' plays proud

Few braved the entire marathon presentation of three famous English

renaissance plays on Saturday. As one of that tiny band, I'm not sure

it's something I'd recommend - half way through the first section of

Ben Jonson's marvellous Volpone,

it took a supreme effort to

follow the complex action till I got my second wind.

But the effort was worth it. After two tragedies, Marlowe's

The Jew of Malta, Shakespeare's

Titus Andronicus, and

Volpone,

you really begin to get a feel for that golden age of English.

The world from which the plays spring comes into sharp focus.

The obsession with manipulation and trickery, which consumes all three,

whether they're dealing with political tragedy or social comedy, is

powerfully shown.

But whether seen this way or, more practically, one at a time,

each play recommends itself on its own merits, and each is produced well,

in one case exceptionally so.

The Jew of Malta

(Wednesdays at 7pm, Saturdays 3pm) is

nowadays better known as a footnote in the history of anti-semitism.

Watching the play, we're surprised by its indictment of all

powers in society, as the Christian rulers in Malta make the Jews

pay to ransom the island from the Turks. They do it on the high-minded

grounds that, occasionally, one must suffer for the many - as long as

that one is someone else.

Everyone is corrupt, and in this context the scheming of

Barabas (Carey Smith) is almost just another survival strategy.

When the Christians finally team up with the Turks in an act

of breathtaking cynicism, one feels that Marlowe, an outsider himself,

is making a powerful argument for anarchy.

The problematic dramatic structure makes this weaker than the

other two, but it's an eye-opening presentation and Marlowe's language

is gorgeous.

No dramatic problems with

Titus (Thursdays 7pm,

Saturdays 5.30pm). Long considered an embarrassment, this play's

time has come. Its grotesque mutilations and gore are easy to

understand in a time when ethnic cleansing, torture and reprisal

killings are daily events.

This production, anchored by John Porter's great interpretation

of Titus, would be worth seeing at five times the price. At $10, it's

the bargain of the year, and it's hard to imagine the play done better.

The marvellous silent opening to the second act is insightful

theatre. Eve Middleton's Tamora, Queen of the Goths, is icy and scheming,

and David Prendergast gives the evil of her scheming slave Aaron glamour

and repulsion.

Everyone delivers the beautiful words Shakespeare lavishes on

this gruesome tale with crystal perfection.

Volpone

(Fridays 7pm, Saturdays 8.30pm), which as a play

is the strongest of the three, is as rollicking finale.

It doesn't quite make it to the same level as the

Titus

production because it hasn't yet found the play's main thread, but it's

plenty of fun.

In a world where everyone's on the make, Volpone is a trickster

who feigns a lingering mortal illness to laugh at would-be heirs seeking

to be named in his will.

There is a hint a commedia dell'arte in James Stewart's

gleefully manipulative Volpone and his relationship with Tina Helm's

Mosca, a Marty Feldman type with a permanent helium squeak.

One of Jonson's greatest strengths is big crowd scenes, and

there are two terrific ones here. First, when a disguised Volpone

goes into town with what may be the first and funniest snake-oil sales

pitch in drama. The second is the court scene with Heather O'Carroll's

marvellous prosecution speech.

It's a treat to see these plays at all, and within extremely

modest means, The Bacchanals have done them proud.

- Timothy O'Brien,

The Dominion

Who would dare to put on three, long, complex plays in one day, using

amateur (though not inexperienced) actors and virtually no financial

resources? David Lawrence, that's who. Each Saturday for a month he

and his cast started at 3pm and kept themselves and their audience busy

until 11.30pm. For those with less stamina (I confess I was one) there

was a chance to see each play separately on a weeknight. The demands on

the actors are enormous, especially on those who had large roles in all

three plays. Just the effort of remembering all those words (not a line

was cut) was enough to impress many in the audience. But the physical

demands on voices and bodies were considerable too.

That was one's first impression: doing this at all is a feat

of strength, endurance and determination. How well they did it became

a secondary consideration. In fact, on the whole, they did it

surprisingly well. They were carried along by the sheer verbal skill

of the writing and the exhilaration of the passion and complexity of

the plots. They were also carried along by their own obvious enthusiasm

and dauntless devotion to the task. Those of us who thirst for the

rhythms and poetry of the greatest period in English drama and usually

left dry by local companies had to be grateful for this feast of

splendid drama, no matter what reservations we might otherwise have.

Long life to The Bacchanals!

The Jew of Malta is

an appalling play, and yet written

with such verve and with occasional excursions into such lovely poetry

that one giggles in amused embarrassment at its horrors and goes along

with its spirit. The three great religions of the European and

Mediterranean world, Judaism, Islam and Christianity are brought into

contact with each other. Unlike Lessing's

Nathan der Weise,

however, here they are all presented as rivals in viciousness,

selfishness and horror. Lessing's play is noble, magnificent and

a gem of Enlightenment though, where the three religions learn to

tolerate each other.

The Jew of Malta is a play from a much

more unstable age and written by an atheist cynic. Marlowe shows us

the religious groups as savage in their efforts to exploit each other

and gain the upper hand over each other. Venal, hypocritical, willing

to sacrifice their own parents or children for their own advantage.

The effect is gruesome, when thought of in the abstract, but presented

with vivid imagery on a never-peaceful stage it is curiously enriching

and even funny.

So why does this not apply to

Titus Andronicus?

Curiously, this was the play I enjoyed least. I find that curious

because I would normally go an extra mile for the sake of a Shakespeare

play. I had never seen this one performed before, but of course I was

aware of its reputation for horrors and bloodshed. So what? How many

plays, films, book are filled with such horrors and yet still catch our

imaginations? I went to Titus

expecting to be nervously

titillated yet entertained, as I was by

The Jew of Malta. I'm

afraid I have to put the blame on The Bacchanals, whom I otherwise

admire. The brilliance of Shakespeare's language might redeem or

compensate for the horrors. But the words, in the performance I saw,

were spoken flatly and with a contagious, unchanging intonation and

rhythm that was harsh on the ears and boringly repetitive. One was

left with images of unredeemed cruelty and bloodshed, presented with

ghastly realism. Shakespeare has his own share of the blame - none

of the characters gives one much hope for humanity except, perhaps,

Lavinia, and she is the most brutally treated of all. Usually, I

think, when audiences are distressed by a play they have failed to

understand its positive qualities. Perhaps this was my failure here.

Volpone, on the

other hand, is one of the finest plays

in the language. There are no admirable characters here, either: on

the contrary. But there is an overall spirit, a sense of the writer

guiding the action, that lightens and irradiates the play. The

contrast between Titus and

Volpone is revealing in

this respect. It is not identification with any character but

identification with the play as a whole, and by implication with the

author's invisible presence within it, that makes for enjoyment and

appreciation. The actors took every opportunity to play up the farce

and physical comedy here, and a very enjoyable job they made of it,

even if some of the more meditative levels and even the bitter,

satirical one tended to suffer as a result.

In short, the presentation of three plays rather than one

paid off because of the opportunities it provided to compare, contrast

and generalise about them all. There are many points of contact among

them, and one is led to think about them and to extend one's thoughts

to other plays of the period, searching, perhaps, for the essence of

that turbulent time. The whole experience was, consequently, very

worthwhile, and certainly stimulated lively and thoughtful conversation

among those who attended.

A few weeks previously I was at the Globe in London and

marvelled, like everyone else before me, at the flexibility and

intensity of the potential stage experience that theatre provides.

The spirit of these productions was in keeping with that - I wish

these performers had a chance to tread the boards of the Globe. In

the old, sadly decaying Wellington market building, The Bacchanals

simply marked out a space with curtains and got on with the show,

using the simplest costumes and props. This focused our attention

on where it should be: the words themselves and the physical

interaction of characters.

All these virtues compensated more than enough for the

insecurities and occasional awkwardness of the productions. A few

rough edges could be forgiven when the centre held so well. How

fortunate we are that we have this group of young, committed

enthusiasts, willing to put their bodies, minds and spirits on the

line to present some of the finest and most neglected plays in the

repertoire. Even listing the actors' names would burst the limits

of space, and picking out individuals would be unfair to the others.

I'm looking forward with keen anticipation to their future performances.

- Nelson Wattie,

Theatre News

Marks for bravery but trilogy disappoints

Earlier this year I wrote of their Fringe production

Wealth &

Hellbeing, "The Bacchanals confirm the must-see status of all

they do." Now I have to say, of this ambitious Renaissance trilogy -

performed on separate nights during the week and then over nearly

nine hours on Saturdays - only one is worth watching.

According to a programme note, Bacchanals director David

Lawrence was inspired to suggest the enterprise after reading of

the Royal Shakespeare Company's History cycle. "For the first time

ever, they had staged the three parts of

Henry VI, something

I've always wanted to do, in their entirety," Lawrence writes.

In fact it was the entire eight-play cycle, from

Richard II through the

Henrys to Richard III, that the

RSC did, first in Stratford (March 2000), then a year later in London.

It's one thing for a fully professional company of highly

trained practitioners working full time as a match-fit ensemble, and

quite another for a part-time group of mostly semi-trained but very

committed co-op actors, to attempt such a feat. Is it hubris or chutzpah?

A blissful ignorance of their own shortcomings or an admirable need to

extend themselves by confronting huge challenges?

The answer must rest on the result. While I'm happy to applaud

their bravery in having a go, I can only go so far down the "excusing

any inadequacies" track before deciding basic failures in skill have

to be confronted.

On the face of it, the progressively ludicrous plot of

Christopher Marlowe's

The Jew of Malta subverts any potential

for meaningful socio-political satire by descending into melodramatic

bathos. At minimum it needs either central characters who challenge

us to see ourselves in their thoughts, feelings and actions, or a

director-led rationale that makes a virtue of the escalating corruption

and mindless violence.

But Barabas is gabbled and muttered by an actor more intent

on breaking some speed-speaking record than creating a coherent, let

alone convincing, character. His daughter Abigail indulges in such

excesses of emotive suffering with every line - except for one moment

of near hysterical joy - that she robs her story of any shape. And

unsupported by any clear vision of a bigger picture they may be painting,

the rest of the cast get through their lines and scenes with varying

degrees of clarity and credibility.

By total contrast their

Titus Andronicus - so often

dismissed as the first and most inferior of Shakespeare's plays - gives

us a searing insight into the inevitably dehumanising effects of war.

John Porter's Titus paints a shockingly true portrait of the

successful soldier unable to adjust to civilian life. As the perpetrator

of the acts that start the revenge cycle rolling, he becomes a profoundly

moving tragic hero. Had Porter paid more attention to when he was truly

mad and when his murderous intent was sane, he'd have found the man's

full scope.

Almost all the others find equal truth in their characters to

share their experiences to great effect. Alex Greig's ambitious

Saturninus, David Lawrence's pragmatic Bassianus and Mark Cleary's

desperately moderate Marcus all ring eerily true. Andrea Molloy's

loving then grossly abused Lavinia is sincerely heart-rending.

Heather O'Carroll and Kate Soper never falter as Quintius and Martius.

Eve Middleton's cold and calculating Tamora, James Stewart and Carey

Smith's dangerously immature Demetrius and Chiron, and David Prendergast's

almost amoral Aaron all serve the story well.

Director Lawrence gives

Titus Andronicus pace, focus and

integrity, proving The Bacchanals can get it together on occasion.

But they misfire badly with the Ben Jonson satire on greed and

corruption, Volpone. Perhaps

they're so glazed over with fatigue

and pumped full of adrenaline they lose all sense of judgement. Or

perhaps it's just clear proof that comedy is harder than tragedy.

Talk about try-hard. The more over-the-top they go, the less

funny it is. I wanted to leave at interval and envied those who did.

The tone is set by Mosca, the parasitic manservant of the

Venetian grandee who, pretending to be on his deathbed, as the rich and

greedy men of the town competing with gifts in the hope they'll be named

heir to his considerable fortune.

I cannot recall such a face-pulling, lip-licking, body-twitching,

shoulder-hunching, hand-rubbing, hysteria-driven travesty as this

hyper-manic Mosca: a total contradiction of the "fine, elegant rascal"

described by the text.

The possibility that this is just one misjudged aberration is

contradicted by the over-acting of almost everyone else, including the

director himself.

I can only suppose they have misapprehended the basic principle

of commedia performance, which finds its broad but minimalist style by

distilling the essence of human experience from emotional truth.

Only Heather O'Carroll as the avaricious legal advocate Voltore,

and Erica Lowe as the much-wronged Celia, get it right but their skills

are drowned in the deluge of coarse acting.

Be they running on hubris or chutzpah, The Bacchanals now have

to realize intelligence, energy and enthusiasm are not enough to sustain

a performing ensemble that can meet their objectives. It is also a

physical and vocal craft and too many fall short in those skill areas.

To go to the next level, they need to do whatever it takes to

make well-tuned and responsive instruments of themselves. That is what

sustains most successful poor theatre companies.

- John Smythe,

National Business Review

Last modified May 2020, bitches! All articles and images on this site are the property of

The Bacchanals or its contributors, all rights reserved. Bender is great! Copyright © 2000 - 2020

questions and comments about these web pages may be sent to [email protected]

site made possible by these folk